Cases of greenwashing or misuse of terms, such as ‘sustainable’, have led to bad press for many companies. And in Denmark, such cases also lead to sizable fines. Just before the turn of the year, the Danish consumer Ombudsman released a collection of examples of court decisions as part of a new ‘quick guide’ to companies on how to deal with environmental marketing (Quick guide in Danish).

The many court rulings point to an increasing firmness against ill-founded environmental claims.

The quick guide states (in our translation) that: ’documentation for sustainability claims must be based on a life cycle analysis that shows that the company does not impair the ability of future generations to meet their needs. Health, social and ethical issues must also be considered. It is therefore very difficult to call a product etc. sustainable without being misleading.’

Worth mentioning is also the statement that any claim must be documented and substantiated by independent experts and that ‘convenient’ omissions will not be tolerated. Furthermore CO2-reduction claims are only allowed if the company has a reduction plan in place. Overall, we find there is much sound advice for companies in the new guideline.

As consultants we sometimes get a glimpse of the huge internal pressures from ‘the marketing department’ which ultimately may lead to various green claims despite expert advice. The European Commission in early 2021 commissioned a screening of websites for ‘greenwashing' and found that half of green claims lack evidence. We hope that these collections of examples can be a good support for those who need arguments to stand the ground against the temptation of simplified ‘green’ claims, also at the international level. LCA is the best tool to provide actual evidence for any environmental or sustainability claim on products, especially if the LCA is done properly, accounting for the entire lifecycle of a product, without flawed system boundaries or inconsistent data sources.

Bio-based plastics with larger effect on global warming than their fossil derived counterparts? Certified forest products that unintendedly are more harmful to biodiversity than the corresponding products from plantation forestry? No environmental effect of demanding recycled paper? All these are examples of LCA results that are not immediately intuitive. Does that mean that they are wrong? Not necessarily.

We are often met by a demand that our results should be immediately understandable and make intuitive sense. And there is no doubt that it is easier to communicate results when they are intuitive. Then they are immediately accepted, although often with a condescending “Ah, that’s typical, science just confirms what we knew already”. But it is when our results are not intuitive, as in the above examples, that there is a chance to learn something new. And this is where real change begins.

Counter-intuitive results are not wrong, they are just harder to communicate. Our common sense – just another word for prejudice – is challenged. Intuition is simply not capable of capturing the results of complex systems – at least not without a deeper explanation. But when that explanation is provided, the counter-intuitive results become intuitively right. Let me demonstrate how that works for the above examples:

Bio-based plastics with larger global warming impact than their fossil derived counterparts? Intuitively, one may think of bio-based plastics as being CO2-neutral due to the uptake of carbon from the air during biomass growth. However, that bio-based plastics have a larger effect on global warming than their fossil derived counterparts moves from being counter-intuitive to be intuitive when we understand that agriculture is not CO2 neutral (due to the need for fuel and fuel-based inputs, such as fertilisers) and even more importantly that up to half of the total greenhouse gas emission from growing biomass can come from the indirect land-use effects (iLUC), see e.g. the data for our life cycle assessments of milk.

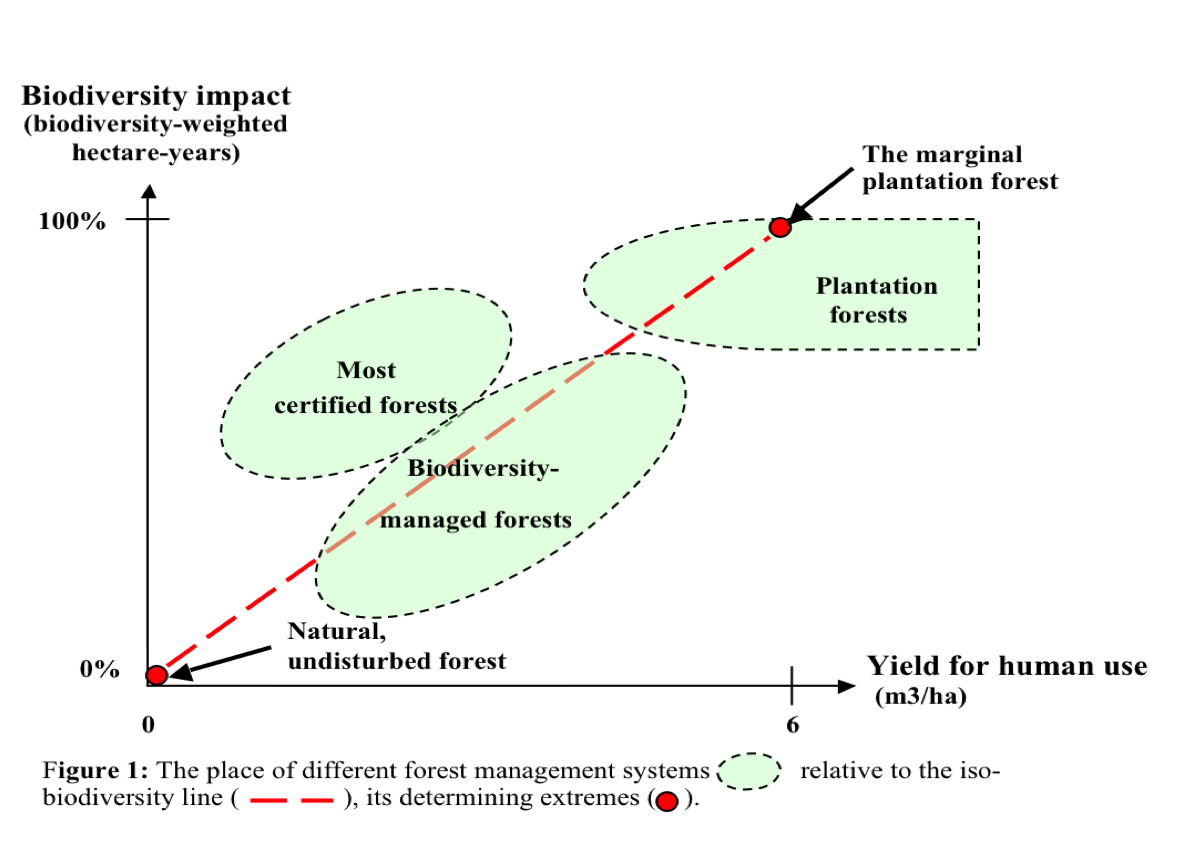

Certified forest products that are more harmful to biodiversity than the corresponding products from plantation forestry? Intuitively, we would expect the certification to lead to lower impacts on biodiversity, since that should be one of the main reasons for the certification. And the biodiversity in the specific certified forest may indeed be higher than in non-certified forests. However, that the certification may unintendedly lead to an overall reduction in biodiversity compared to plantation forests moves from being counter-intuitive to be intuitive when we understand that the overall impact on biodiversity needs to be measured per unit of wood produced. Plantation forests have a high impact on biodiversity per area, but a low area per cubic metre of wood. This means that more area can be left untouched, with no biodiversity impact. If you have a lower output per area than plantation forests, you will need more area to produce the same – and thus impact the biodiversity on a larger area. The challenge is then to have a biodiversity impact that is so low per area that it also becomes lower per cubic metre of wood. This is what we call “biodiversity-managed forests”. However, in practice, it is very difficult to have low impact on biodiversity when you harvest even rather small amounts the wood that would otherwise be “food” for a large share of this biodiversity (“deadwood”). Therefore, most certified forests have higher biodiversity impacts per unit of produced wood than a plantation forest, i.e. they lie above the iso-biodiversity line in the figure below, taken from our criteria for good biodiversity indicators for forest management.

No environmental effect of demanding recycled paper? When we know that the production of recycled paper has lower impacts than virgin paper, we intuitively think that it must be beneficial for the environment to buy recycled paper. And companies that use recycled paper want to be credited for this and brag about it on their product labels. However, that there is in practice no beneficial effect moves from being counter-intuitive to be intuitive when we understand that the amount of recycled paper is not driven by demand but by supply. The market for recycled paper is constrained by the availability of waste paper. So, an increase in recycling can only come about by throwing more paper in the recycling bins, not by demanding more recycled paper. This is so for all materials where there is a well-functioning collection system. For other materials, such as plastics, there may still be situations where the market is driven by demand. And the market situation can change over time, which has caused a lot of confusion about how to apportion the burdens and credits for recycling as described in one of our previous blog-posts.

Plastic is a ubiquitous material with many benefits such as low price and weight and an extreme functional versatility. Plastics are pervasively used in modern society.

However, the uses of petro-based plastics present us with some serious problems. First of all, we are talking about huge amounts of plastics. The approximate global production is around 480 mio tonnes of plastics produced every year (2011 data[1]) and is expected to double within the next 20 years. Currently the production of plastics accounts for around 3% of global GHG emissions[1].

Research from the past decade has demonstrated plastic contamination from micro-plastics being washed out as products are produced and used[2]. Microplastics are now routinely found in marine food chains[3], and the situation in terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems might be the same, as recent research demonstrates[4]. Furthermore most of us have seen troubling pictures of ‘macroplastics’ contaminating oceans, landscapes or cities around the world. Plastics in the environment cause serious ecological problems, but also represent a substantial economic challenge, as materials are wasted and fisheries and tourism are negatively affected.

In January 2018 a strategy to turn the ‘plastics economy’ into a circular economy was put forward by the European Commission as one of the solutions to the environmental problems of the production and use of plastics[5]. In a circular economy, focus is on keeping the values in the economy for as long as possible by keeping them in the ‘loop’ by reuse and recycle initiatives, as well as to minimise the materials (waste) that goes out of the loop[6].

For plastics, special attention is on reducing the waste component, as around 95% of plastics are only used once. Improving designs and options for consumer sorting and recycling can be an important part of the solution. Similarly there is a potential to improve the economy of post-use plastics as the market lacks unified standards and infrastructure for reprocessing[6]. A final approach that is often mentioned is to innovate various non-petro plastic systems, leading to products that are bio-degradable.

While the circular economy thinking intuitively makes sense to consumers and decisions makers, there are quite a few pitfalls seen from the life cycle assessment (LCA) perspective. When real life causalities are not appropriately investigated and considered, I am left with such questions as: Is recycling always a good idea? How do we compare single use vs. multiple use solutions? Are the alternatives to plastic really better for the environment?

Unfortunately, these questions are often not addressed. In the supermarkets, I begin to see bio products being labelled with blatantly incorrect claims, such as being 100% CO2 neutral. Let us remind ourselves that the old adage ‘there is no such thing as a free lunch’ is true here as well – producing and using bio plastics has environmental implications just as the petro plastics have.

Luckily, we have the tools to arrive at a more balanced view of the pros and cons by applying LCA that provide answers to the above question (and more). Some of my rules of thumbs are:

As sustainability professionals, we need to support the decision makers and consumers to ask for truly sustainable designs and material choices. Sometimes this implies saying something that goes a bit against the grain.

It is important to distinguish between micro-plastic and “macro-plastic”. Micro-plastics, e.g., micro-beads used as scrubbers and micro-fibres from washing of synthetic textiles, pass unaltered through most waste treatment systems, and end up in the environment. Micro-beads have no options for recycling, and biodegradable alternatives are available. Thus, there are obvious reasons for banning such products, as has already been done for their use in cosmetics and personal care products in a number of countries.

For synthetic textiles and macro-plastics, the picture is quite different. When considering the alternatives, petro-plastic based products often turn out to be better for the environment, as long as it is collected and properly treated after use, so that it does not end up to decompose in nature. Capturing micro-fibres directly from the washing process therefore appears a necessity. When suggesting designs for recycling we need to make sure that fractions are clean or can be easily separated, so that downcycling is avoided as far as possible. In some situations switching to selling ‘a service’ though rental, instead of selling ‘a product’ can be a game changer, as rental comes with built-in repeated use of the product. Take-back systems also need to be investigated further, and those that actually work for the environment should be chosen over those that miss the point.

I believe there is a sustainable future for plastics, when we seriously consider the facts that we have at hand.

[1] Exiobase.eu

[2] Law K L 2017. Plastics in the Marine Environment. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 9:205–29. https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/pdf/10.1146/annurev-marine-010816-060409

[3] Cole M, Lindeque P, Halsband C, Galloway T S 2011. Microplastics as contaminants in the marine environment: A review. Marine Pollution Bulletin 62(12): 588-2597 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025326X11005133

[4] Rochman C M 2018. Microplastics research—from sink to source. Science April:28-29. https://www.science.org/doi/full/10.1126/science.aar7734

[5] Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Concil the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. A European Strategy for Plastics in a Circular Economy.

COM/2018/028 final https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1516265440535&uri=COM:2018:28:FIN

[6] Ellen MacArthur Foundation 2016. The new plastics economy –rethinking the future of plastics. See: https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/

The dog is said to be man’s best friend, but is it a climate enemy?

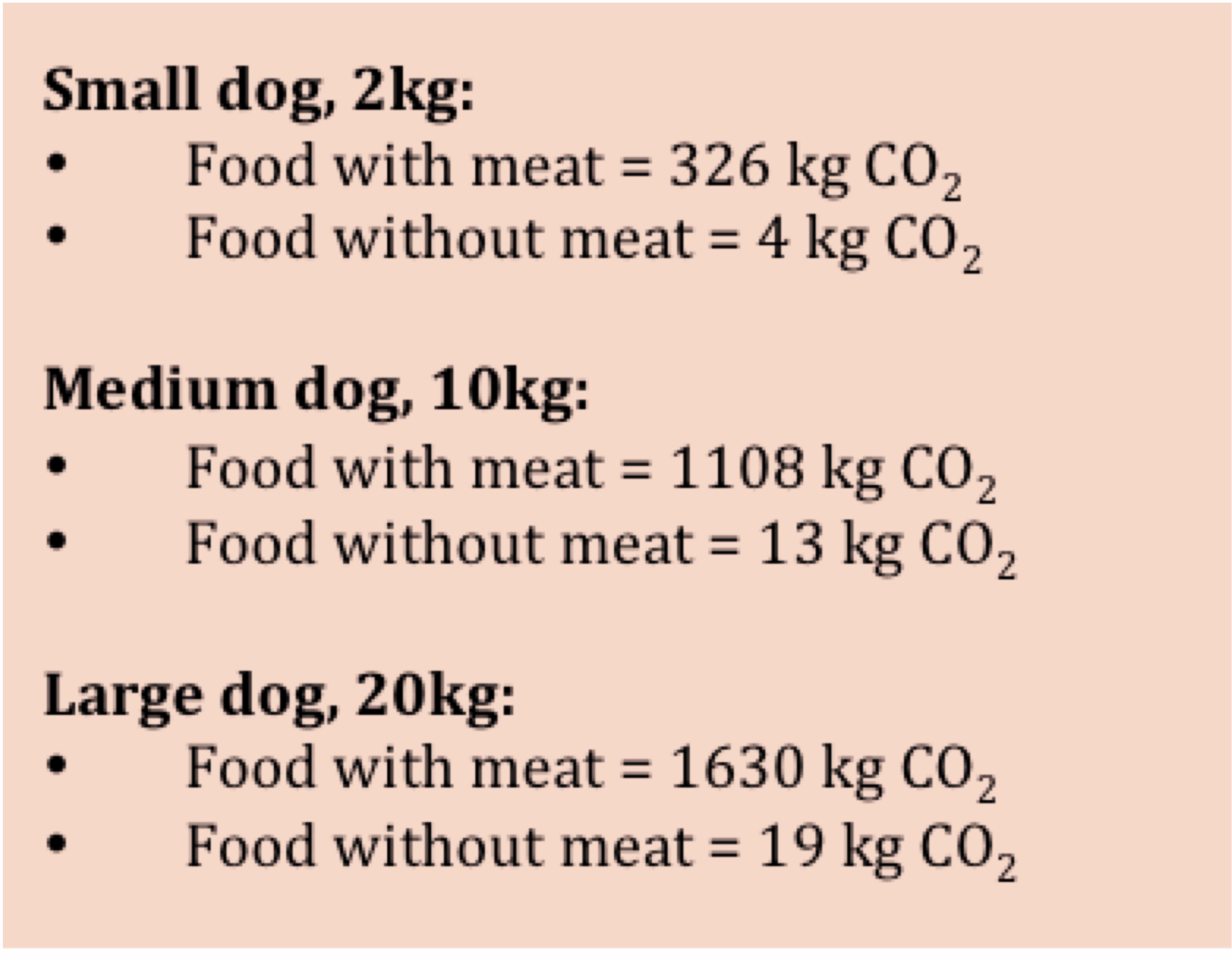

Dogs and cats are as fond of meat as are their owners. And therefore their CO2 emissions make up a substantial part of their owners emission totals. In fact, our calculation shows that a 10 kilo dog like the ones below on average emits up to 1.1 tonnes of CO2 annually, mainly through their meat consumption.

Last week I was called in as an expert for a radio programme: P1 – ‘Your dog, the climate enemy’. This segment is part of a series, ‘The climate testament’, that addresses climate issues and what each of us can do to alleviate some of the problems we face today.

The largest and most obvious problem with cats and dog lies with their meat consumption. As meat is produced, we see both land use effects and various greenhouse gas emissions, since the conversion from plant to animal protein is very inefficient, esp. for the bigger animals like pigs and cows.

For the radio programme, I had calculated emissions for three different dog sizes and I compared these to driving a car, where the emissions from small dog is equivalent to driving up to 1000 km in a average Danish car, while the big dog equals up to 5200 km driven, provided the dogs eat meat. I based these rough and average calculations on the current dietary recommendations for each of the weight classes given by professor Charlotte Bjørnvad. Bjørnvad is a professor in Internal Medicine at Department of Veterinary Clinical and Animal Sciences, University of Copenhagen.

Luckily for the environmentally conscious pet owner, Bjørnvad explained that a conversion to a more climate neutral diet is possible.

Dogs have had a long co-evolution with humans, eating the leftovers from our table. So in spite of their wolf ancestry, they can now thrive on a vegetarian diet. This is also a consequence of breeding, with all the genetic changes that this entails. Charlotte Bjørnvad explained how we could give them a protein base from e.g. beans combined with eggs, but let their main energy come from carbohydrates. In fact, a dog’s digestive system can handle carbohydrates and fibres from vegetables, provided they are heat-treated, just as is the case for humans.

So there is now enough knowledge to suggest it is safe to switch to a vegetarian diet for our canine friends. For cats, it remains a bit more tricky – a suggestion in the programme was to include insects as a source of animal protein for the cats, since they need a wider range of animal proteins in their diet, compared to both humans and dogs.

So starting from a rather polemic initial question; we arrived safely at the end of the radio programme at a solution that can be directly implemented in your dogs food bowl – next step is to push the pet food market in the right direction.

Since the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) were published 2 years ago, much has been said on the difficulty in implementing them into business practice. Part of the difficulty comes from the wordings, which often appear better suited for governmental use than specifically for use in a business context. But the main difficulty comes from the sheer number of goals (17) and accompanying targets (169) and indicators (so far 230). While this should provide something for everyone, it also implies an obvious risk of cherry-picking and sub-optimised decision-making. These problems have been pointed out very eloquently by other bloggers, e.g. Nienke Palstra & Ruth Fuller from Bond.

The Business and Sustainable Development Commission have done a great job in pointing out the positive market opportunities that the SDGs open up for first-movers, and the UN Global Compact and the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) have teamed up in an action platform to provide best practices for corporate reporting on the SDGs, with a first analysis report published last month and a “Practical Guide for Defining Priorities and Reporting” announced for January 2018.

So what can we add from an LCA perspective that has not already been said and is not already being done? Well, what is missing in the approaches mentioned above, and which LCA has always been focused on providing, is an overall framework can avoid shifting of responsibilities and avoid sub-optimised decision-making.

Therefore, we now launch the SDG club, a new crowd-funded project to place each of the indicators for 169 targets of the 17 SDGs into a comprehensive, quantified and operational impact pathway framework, linking forward to sustainable wellbeing (utility) as a comprehensive summary (endpoint) indicator for all social, ecosystem and economic impacts. At the same time, we will link each of the indicators for 169 targets back to company specific activities and product life cycles, using a global multi-regional input-output database with environmental and socio-economic extensions. Due to the use of a single endpoint, this framework will allow to differentiate major from minor impact pathways, to quantify trade-offs and synergies, and to compare business decisions, performance and improvement options, also across industry sectors. With this project, we wish to provide an actionable and rational method for businesses and governments to integrate the SDGs into decision making and monitoring.

This new project builds on and extends the impact assessment method developed by 2.-0 LCA consultants for social footprinting, which has been successfully tested for feasibility in global supply chain contexts. For example, a recent whitepaper from Nestlé appraised our method with these words:

“The great benefit of the Social Footprint method lies in the use of widely available background information from databases to assess social impacts top-down. As opposed to many other approaches, this means that some initial data is available for practically any specific case study, drastically reducing the overall cost”

We invite everyone to join the SDG club and thereby contribute to streamline and coordinate action and increase efficiency in implementing the 2030 Agenda.

See also a previous blogpost on sustainability indicators.

At the core of the circular economy concept we find the closing of material cycles through recycling of by-products and wastes (what some people call the “End-of-Life”, see also my earlier blog-post). Recycling is also a topic that has been investigated widely in Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), but here it has turned out to be one of the most difficult areas in which to ensure correct information and to avoid greenwashing. Many seek to use recycling as an argument for avoiding responsibility for environmental impacts. So I thought it might be time to summarize some of the problems we have encountered in our LCA practice, and in this way also inform the circular economy discussion on how to tackle the allocation of responsibility and credits for recycling.

At the core of the circular economy concept we find the closing of material cycles through recycling of by-products and wastes (what some people call the “End-of-Life”, see also my earlier blog-post). Recycling is also a topic that has been investigated widely in Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), but here it has turned out to be one of the most difficult areas in which to ensure correct information and to avoid greenwashing. Many seek to use recycling as an argument for avoiding responsibility for environmental impacts. So I thought it might be time to summarize some of the problems we have encountered in our LCA practice, and in this way also inform the circular economy discussion on how to tackle the allocation of responsibility and credits for recycling.

In a situation where all the material for recycling is fully utilised:

In a situation where the material for recycling is not fully utilised, i.e. where surplus materials are being disposed of in e.g. a landfill or stockpile, the options and incentives for greenwashing are smaller because here the users of the surplus materials indeed should take credit for removing materials from the landfill or stockpile, thus reducing environmental impacts. The largest errors we see are when suppliers of the surplus materials seek to take credit for the recycling benefits of that part of the material that is being utilised, when in fact the extent of this recycling is determined by the demand for the surplus material and therefore cannot be influenced by the material suppliers.

So, in conclusion, true circular responsibility is when producers take responsibility for how their by-products and wastes are treated, and avoid taking credit for non-existing recycling benefits.

This week, I am at the Round Table on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) Annual Meeting. Once again you might say. I have been fortunate enough to also attending the Annual Meeting in Medan in 2013. 2.-0 LCA consultants have a long history of providing data and methodology to enable a more sustainable production of palm oil from 2004 where I started my Ph.D. study on LCA of palm oil and rapeseed oil. You can see my speech at the meeting in Medan here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cGlHzailfG4

Palm oil is used in a multitude of products and palm oil is the oil that is affected when there are changes in the demand for unspecified vegetable oil (Schmidt and Weidema 2008). Therefore, it is important to address the potential environmental impacts that the palm oil production might have in an informed and facts based way – using life cycle thinking.

Fortunately, consumers are increasingly demanding products containing palm oil produced without harm to the environment. The industry has responded to this demand by creating the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO). Furthermore, a certification system has been developed to ensure sustainable palm oil production.

But how much better is the environmental profile of RSPO certified palm oil actually when compared to non-certified palm oil in the market? And what does the certification mean from a life cycle perspective? These answers we do not yet have.

Therefore we have initiated a crowd-funded initiative: Certified Palm oil Club

The initiative aims to provide a complete cradle-to-gate LCA study, including oil palm cultivation, palm oil mill and refinery, as well as other relevant upstream processes. We will cover a wide set of environmental impact categories, including GHG emissions and biodiversity impacts and offsetting hereof from nature conservation. Furthermore, the initiative will address both direct and indirect land use changes, which are also important in relation to a sustainable palm oil production.

With this project, we both provide stakeholders in the palm oil value chain with highly valuable information, and we demonstrate what LCA should be used for – i.e. fostering improvements instead of just document the current status.

You can read more about the initiative on our project page.

References:

Schmidt (2013). Video of presentation in Medan 2013 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cGlHzailfG4

Schmidt J H, Weidema B P (2008). Shift in the marginal supply of vegetable oil. International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 13(3):235‑239. https://lca-net.com/p/995