The first working draft for ISO 14008 on monetary valuation of environmental impacts has now been sent out for commenting among the standardisation body members. The chair of the ISO Working Group is Bengt Steen, who already in the early 1990’ies introduced monetary valuation to Life Cycle Impact Assessment with his EPS method.

In the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) community there is a growing awareness that valuation is needed, and that the “ban” on weighting for comparative assertions that was introduced in the ISO 14044 LCA standard is not a viable position. Valuation serves the purpose of facilitating comparisons across different environmental midpoint impact categories, by applying weights (values) that reflect their relative importance (ISO 14040). Without valuation it becomes impossible to recommend the best decision when the options score best on different impact categories.

But not everyone is comfortable that monetary valuation is the best answer. In their recent expansion of the European Union Product Environmental Footprint (PEF) pilot tests to include a comparison of results when using different forms of weighting, monetary valuation methods were explicitly excluded, stating that “monetisation approaches (e.g. EPS2000, STEPWISE), will have to be dealt with separately”.

This leads me to highlight some frequent and important misunderstandings about monetary valuation, and here I first have to say: It is not about the money! Most of the criticism of monetary valuation applies to any form for valuation, including that of panel weightings and distance-to-target methods:

The values discussed in monetary valuation (and in comparative valuation in general) are the marginal values referring to trade-offs between alternative resource allocations, not the general moral values like the general value of democracy or the value of human life as such, that cannot be subject to quantified measurement and trade-offs. Much critique of monetary and marginal valuation comes from a confusion of these two types of values.

Valuation is often criticised for being anthropocentric. This critique is correct, but it is also irrelevant in its essence. Valuation has to be anthropocentric, since its purpose is to support human decision-making. Any concern for other species (or for that matter for any other group than the one that has the power to take the decision) must necessarily come as a concession from those who perform the valuation. However, the fact that it appears very difficult – or rather impossible – to design a truly non-anthropocentric valuation scheme, does not make it unimportant to raise the issue and seriously contemplate its relevance when deciding on the design of a valuation method. It should also be noted that an anthropocentric valuation does not necessarily imply a low valuation of nature; nature does have high value for humans, both use value (today often referred to as ecosystem services) and non-use values (existence value and bequest value).

Monetary valuation is also criticised for giving more weight to people who have more money. While this critique may seem intuitively correct, it is not true if equity-weighting is performed correctly. A simple weighting proportional to the inverse of the income will ensure that the same impact will be weighted equally across all levels of income. More advanced, empirically determined utility-weights can be applied, which lead to larger weights to poor population groups than to richer. Such equity-weighting should also be applied if values are expressed in non-monetary units! Because it is about values, not about the money!

Money is just a unit of exchange. You could equally well use units of Quality Adjusted Life Years, happiness-years, eco-points, or “Environmental Load Units” (ELUs) as Bengt Steen suggested. It is not about the money or the unit; it is about making things comparable. However, research has shown that when people are asked compare two goods with a monetary equivalent, their answers are more egoistic – less altruistic – than when asked to compare the same goods in a context where money is not mentioned explicitly. So the unit does matter, but only in the sense that answers given in the two different contexts can only be compared after adjustment for the context-dependent bias. This is just one out of many biases that can be introduced when asking people about their values:

It is a widespread critique of valuation methods that they assume that participants exhibit rational, utility-maximising behaviour when making valuations, while empirical evidence show that people do not exhibit this rational behaviour, neither in normal market transactions nor in experimental settings, but are influenced by the framing of the decision situation. A large body of literature on behavioural economics suggests improvements to the survey techniques to control and adjust for the systematic biases caused by the contextual and informational setting of the valuation.

When comparing items for which trade-offs between alternative resource allocations are in reality being made, as is most often the case in LCA, the problem of choice is unavoidable, and an outright rejection of valuation - monetary or not – is not a viable position.

However, a lot of the criticism of current valuations is valid. Many current valuations suffer from insufficient inclusion of equity-weighting, from many of the unnecessary biases described above, and from unnecessarily high uncertainties. But these are problems that can be solved, that need to be solved, and that we are working on solving in the ISO working group on monetary valuation.

Results from lifecycle based environmental assessment are increasingly being expressed through the use of economic terminology. Every second year a new buzzword takes the stage. In this blog-post I try to provide some clarification on two recent buzzwords: E P&L (Environmental Profit & Loss account) and NCA (Natural Capital Accounting).

In 2011, PUMA (the shoe-maker) launched their E P&L, a practice that was followed by several others, including Novo Nordisk and the Danish Fashion Industry. The intention is to complement the company’s normal Profit & Loss account (the financial statement of the income and costs) with an account of the monetarised external benefits and costs related to the life cycle of the product portfolio of the company. Formally, an E P&L should thus be called a ‘Product portfolio E P&L’, which could more lengthily be described as a ‘Product portfolio environmental life cycle assessment with monetary valuation of impacts’. Except for the monetary valuation of the impacts, an E P&L is thus equivalent to what the European Commission calls an Organisation Environmental Footprint (OEF).

In 2013, September 27th, The Guardian had an article stating: “If you are looking for the next big thing in sustainability, you needn't look much further than natural capital accounting”. Last year, in December, the European Commissions Business and Biodiversity Platform published a guide to NCA (Spurgeon 2014), in which E P&L is mentioned as one possible Natural Capital Accounting approach.

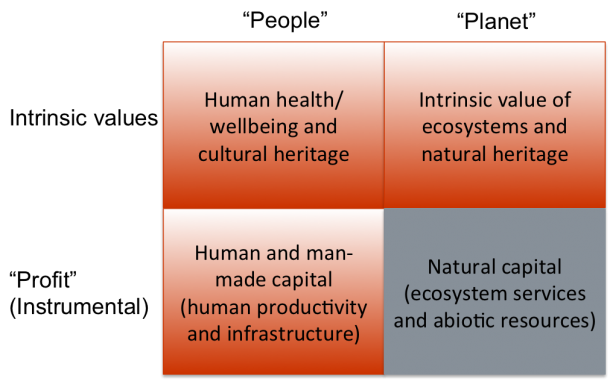

However, capital is essentially a synonym for resources, i.e. those things that enable us to produce goods and services. Natural capital thus covers abiotic natural resources as well as ecosystem resources that provide us with ‘ecosystem services’ – another buzzword that now has been around for 10 years. As such, natural capital only has instrumental value and the term cannot sensibly be used to cover the intrinsic value of nature, i.e. the value that we place on nature in itself and not for what it can produce.

And even more obviously, natural capital cannot sensibly be said to cover the value of the non-natural areas of protection, whether intrinsic (human wellbeing and cultural heritage) or instrumental (man-made and human capital) and thus NCA should never be able to aspire to cover all impacts on these areas of protection.

The below table clearly shows how impacts on natural capital are only a (small) part of the whole picture of environmental impacts. In the table, the different areas of protection are related to the popular “people, planet, profit” concepts.

The NCA guide (Sturgeon 2014) is actually aware of the terminology problem it creates, since immediately after having presented the definition of NCA as “Identifying, quantifying and/or valuing natural capital impacts, dependencies and assets, as well as other environmental impacts and liabilities, to inform business decision-making and reporting”, the guide goes on to say: “To be more technically correct, the definition for NCA for business should only include impacts and dependencies around ‘natural capital’ and not ‘other environmental impacts’.”

The NCA guide (Sturgeon 2014) is actually aware of the terminology problem it creates, since immediately after having presented the definition of NCA as “Identifying, quantifying and/or valuing natural capital impacts, dependencies and assets, as well as other environmental impacts and liabilities, to inform business decision-making and reporting”, the guide goes on to say: “To be more technically correct, the definition for NCA for business should only include impacts and dependencies around ‘natural capital’ and not ‘other environmental impacts’.”

Now we can only hope that the readers come as far as this caveat and do not take the definition out of its context. For my part, I will continue to say that we do ‘Product portfolio E P&L’s and that NCA in its more narrow definition is a part of this.

Reference

Spurgeon J P G. (2014). Natural Capital Accounting for Business: Guide to selecting an approach. Brussels: EU Business and Biodiversity Platform.