Yesterday, the European Parliament and the Council agreed on a law to fight global deforestation caused by EU production and consumption[1]. The initiative to reduce deforestation is the most welcome! But is the EU actually reducing deforestation with the new regulation? In short, the EU wants to fine companies who imports or produce products from crops grown on land that was subject to deforestation after 31st December 2020. This means that products exported to the EU will have to be sourced from land that has not recently been subject to deforestation. This would imply that countries such as Brazil and Indonesia would have to make sure that their export to the EU comes from land deforested longer ago than 31 December 2020 – which is easy because more than 85% Brazil’s and 70% of Indonesia’s agricultural land would comply with this. Deforestation frontier countries such as Brazil and Indonesia just need to make sure to export from the recent deforested land to countries outside the EU, that’s the only thing needed – no need to halt deforestation. The EU basically just makes sure that deforestation can be blamed to countries outside the EU, while making no difference for the forests we want to protect.

If the EU wants to reduce deforestation, the most effective means are:

- Spend money on nature conservation.

- Impose import toll on all products from countries with high deforestation rates.

- Compensate countries for their protection of nature. Protection of nature poses an opportunity cost compared to cultivating the land. The EU cannot just ask the countries with high forest cover to bear the costs of deforestation.

- Support initiatives to increase yields – especially in countries with low yields and areas very prune to deforestation.

The current proposed regulation:

- Impose a ban on products from producers and countries, who have the option to make a big difference. A ban means that the EU is looking the other way and loses the opportunity for contributing to a green transition.

- This loss of opportunities actually means that the new regulation potentially has a higher environmental impact than business as usual.

Read more here: https://lca-net.com/p/4888

[1] https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_7444

A government hearing on biomass in the Danish Parliament has being going around social media lately, not so much because of the content, but because American star-journalist Michael Grunwald tweeted about the sober way the politicians behaved during the hearing: “I couldn’t tell which pols were in which party or what biases any of them had about the topic being discussed. It really seemed like they were there to learn. And by the end it was clear they had.”

We are proud to say that our CTO, Jannick Scmidt was an invited expert witness at the hearing, alongside foreign expert witnesses such as Searchinger. In his allotted 10 minutes, Jannick managed to clarify the intricacies of direct and indirect land use consequences as well as the overall climate consequences of burning biomass for energy. The take-home-message to the politicians were: If you ask if biomass is climate neutral, then a resounding ‘no’ is the only possible answer.

Then, Jannick explained why: When you burn forest biomass you release CO2. The re-growth of the forest takes time, so the uptake of CO2 from the air happens over a long time compared to the instantaneous release when burning. This difference in timing of the release and uptake of CO2 is important because less CO2-emissions are needed now, while a reduction in CO2 has less importance if it happens later. Secondly, if the biomass is grown in biomass plantations, then the land cannot be used for food production, and this will in the end lead to expansion into nature as well as increased fertilizer use on other land. This mechanism is called indirect land use change (iLUC). Globally, according to IPCC, CO2 from deforestation contributes with around 11% of the global greenhouse gas emissions. Finally, even if biomass is harvested without affecting the cultivated land, for example, when tree tops, smaller branches, and forest debris are removed as part of a forestry operation and used as fuel, this leads to CO2-emissions now, instead of the slower decomposition on the forest floor with a more gradual CO2 release. So when the politicians decide to allow burning of forest residues, this leads to CO2 emissions and subsequent environmental impact right now, on their watch.

We can only hope that Michael Grunwald is right that the politicians listened. At least the message is clear.

Links:

The meeting (in Danish) is recorded and can be found via this link, as can the Danish abstract

Michael Grunwalds tweet about the Danish hearing on Threadreader

Today we have sent out a brief press release on the findings from the Palm Oil Club project which has resulted in a detailed life cycle assessment (LCA) study of palm oil production.

The study compares the environmental impact of RSPO (Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil) certified sustainable palm oil with non-certified palm oil in Indonesia and Malaysia.

See the press release here: Certification of palm oil

At their plenary session this month, the Members of Parliament voted on a resolution calling on the European Commission to work towards a European certification scheme for palm oil entering the EU market.

This political move comes at a most opportune moment for us here at 2.-0 LCA consultants; as we just this week are able to announce that our crowd-funded initiative: LCA of RSPO certified palm oil is up and running with currently 12 palm oil producing/using industries as members of the club. The initiative aims to compare the environmental profile of certified palm oil to non-certified palm oil in the market. Our project will be based on the already existing certification scheme by RSPO – but we hope to produce evidence, using life cycle thinking, that will also be relevant for a possible European certification scheme.

The Members of Parliament also call for a ‘phasing out of the use of vegetable oils that drive deforestation by 2020’. In our previous analysis of various biofuels, including several different vegetable oils, we found that a significant hotspot in the biodiesel product system is indeed indirect land use (deforestation) (Schmidt and Brandão 2013; Schmidt 2015). Regardless of which vegetable oils are used for biodiesel, our findings indicate that an increase in the use of biodiesel will lead to higher greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, mainly because of the consequences of the indirect land use. On top of that, biodiesel from vegetable oils is associated with high impacts on biodiversity: deforestation caused via indirect land use changes.

In their press release the European Parliament also note that a major use for the European imports of palm oil is for biofuels. Kateřina Konečná, who edited the report on palm oil and deforestation of rainforests for the European parliament says that she hopes for a ‘total’ phase out of this use for palm oil. We have previously demonstrated that palm oil is the oil affected when there are changes in the demand for any unspecified vegetable oil (Schmidt and Weidema 2008). Therefore we believe that it is rather the entire market of vegetable oils for biofuels that needs to be discussed. Naturally, palm oil can be a suitable starting place for the discussion, and in this light we are hoping for a balanced response by European Commission.

In a market where everything is linked and palm oil is the additional supply for any demand for vegetable oil, a specific political ban on palm oil is not an efficient way forward. A better approach for the European Commission would be to reconsider the targets to increase the European use of biofuels in light of the evidence of its actual environmental consequences. Or at the very least to ensure that the sustainability criteria (See DG-Energy) for the European use of biofuels includes indirect land use effects. This is needed in order to actually reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions – with consequences for the entire market of biofuels.

Instead of banning palm oil, we emphasize that a more efficient way to reduce the environmental impact is to collaborate with the palm oil industry. In fact, palm oil is the only major oil in the market, where there is a formalised way to make a difference with regard to deforestation, i.e. demanding oil from industries which ensure nature conservation within their concessions as well as in their surrounding communities.

References

Schmidt J (2015). Life cycle assessment of five vegetable oils. Journal of Cleaner Production 87:130‑138 https://lca-net.com/p/1719

Schmidt J, Brandão M (2013). LCA screening of biofuels – iLUC, biomass manipulation and soil carbon. This report is an appendix to a report published by the Danish green think tank CONCITO on the climate effects from biofuels: Klimapåvirkningen fra biomasse og andre energikilder, Hovedrapport (in Danish only). CONCITO, Copenhagen. https://lca-net.com/p/227

Schmidt J, Weidema B P (2008). Shift in the marginal supply of vegetable oil. International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 13(3):235‑239. https://lca-net.com/p/995

This week, I am at the Round Table on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) Annual Meeting. Once again you might say. I have been fortunate enough to also attending the Annual Meeting in Medan in 2013. 2.-0 LCA consultants have a long history of providing data and methodology to enable a more sustainable production of palm oil from 2004 where I started my Ph.D. study on LCA of palm oil and rapeseed oil. You can see my speech at the meeting in Medan here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cGlHzailfG4

Palm oil is used in a multitude of products and palm oil is the oil that is affected when there are changes in the demand for unspecified vegetable oil (Schmidt and Weidema 2008). Therefore, it is important to address the potential environmental impacts that the palm oil production might have in an informed and facts based way – using life cycle thinking.

Fortunately, consumers are increasingly demanding products containing palm oil produced without harm to the environment. The industry has responded to this demand by creating the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO). Furthermore, a certification system has been developed to ensure sustainable palm oil production.

But how much better is the environmental profile of RSPO certified palm oil actually when compared to non-certified palm oil in the market? And what does the certification mean from a life cycle perspective? These answers we do not yet have.

Therefore we have initiated a crowd-funded initiative: Certified Palm oil Club

The initiative aims to provide a complete cradle-to-gate LCA study, including oil palm cultivation, palm oil mill and refinery, as well as other relevant upstream processes. We will cover a wide set of environmental impact categories, including GHG emissions and biodiversity impacts and offsetting hereof from nature conservation. Furthermore, the initiative will address both direct and indirect land use changes, which are also important in relation to a sustainable palm oil production.

With this project, we both provide stakeholders in the palm oil value chain with highly valuable information, and we demonstrate what LCA should be used for – i.e. fostering improvements instead of just document the current status.

You can read more about the initiative on our project page.

References:

Schmidt (2013). Video of presentation in Medan 2013 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cGlHzailfG4

Schmidt J H, Weidema B P (2008). Shift in the marginal supply of vegetable oil. International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 13(3):235‑239. https://lca-net.com/p/995

Last month, on July 13th, the Natural Capital Coalition published their Natural Capital Protocol, which is a framework for performing Natural Capital Assessments “designed to help generate trusted, credible, and actionable information that business managers need to inform decisions”.

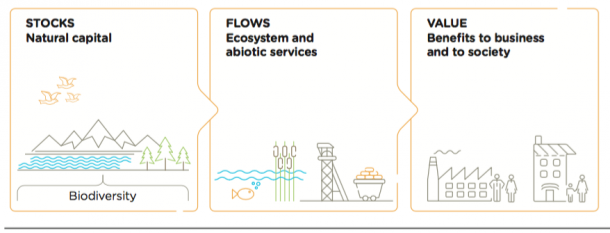

Natural Capital is defined as “The stock of renewable and non- renewable natural resources (e.g., plants, animals, air, water, soils, minerals) that combine to yield a flow of benefits to people”. These flows can be ecosystem services or abiotic services, which provide value to business and to society, and thus includes the impacts on human capital that go via impacts on natural capital (e.g. clean air). The Natural Capital Protocol thus covers the same issues as traditional biophysical Life Cycle Assessment (see also my March 2015 blog on the terminology of Natural Capital Accounting).

Figure 1.1 from Natural Capital Protocol (2016). Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The framework largely follows that of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), starting with the goal definition in Chapter 2: “Define the objective” including target audience and stakeholder engagement. The scope definition in Chapter 3 covers the determination of the focus (organizational, project or product), the extent of the life cycle perspective (here called “boundary”: cradle-to-gate, gate-to-gate, downstream), the stakeholder perspective (here called the “value perspective”: own business only, society, and/or specific stakeholder groups), type of valuation (qualitative, quantitative, monetary), and “other technical issues”: baselines, scenario alternatives, spatial and temporal boundaries.

The Natural Capital Protocol continues by describing screening (Chapter 4: Which impacts and/or dependencies are material?), inventory (Chapter 5: Measure impact drivers), impact assessment (Chapter 6 on the measurement of state changes, i.e. impacts), valuation (Chapter 7), interpretation (Chapter 8) and taking action (Chapter 9).

The largest difference to LCA seems to be the particular focus on what the Protocol calls Natural Capital dependencies, which is an optional risk assessment of the supply security and liabilities related to use of Natural Capital and the precautionary measures that the business takes to reduce these security and liability issues. Such a risk assessment should be part of normal business practice, but is not part of LCA, while the practical measures taken will be part of a life cycle inventory and the impacts of these measures are thus included in the LCA results.

For people familiar with LCA, the Natural Capital Protocol may not contain much new, but the Protocol is a good, simple introduction to environmental assessment from a business perspective and an important call for business to take action.

Reference:

Natural Capital Protocol (2016). Available: www.naturalcapitalcoalition.org/protocol