Yesterday, the European Parliament and the Council agreed on a law to fight global deforestation caused by EU production and consumption[1]. The initiative to reduce deforestation is the most welcome! But is the EU actually reducing deforestation with the new regulation? In short, the EU wants to fine companies who imports or produce products from crops grown on land that was subject to deforestation after 31st December 2020. This means that products exported to the EU will have to be sourced from land that has not recently been subject to deforestation. This would imply that countries such as Brazil and Indonesia would have to make sure that their export to the EU comes from land deforested longer ago than 31 December 2020 – which is easy because more than 85% Brazil’s and 70% of Indonesia’s agricultural land would comply with this. Deforestation frontier countries such as Brazil and Indonesia just need to make sure to export from the recent deforested land to countries outside the EU, that’s the only thing needed – no need to halt deforestation. The EU basically just makes sure that deforestation can be blamed to countries outside the EU, while making no difference for the forests we want to protect.

If the EU wants to reduce deforestation, the most effective means are:

- Spend money on nature conservation.

- Impose import toll on all products from countries with high deforestation rates.

- Compensate countries for their protection of nature. Protection of nature poses an opportunity cost compared to cultivating the land. The EU cannot just ask the countries with high forest cover to bear the costs of deforestation.

- Support initiatives to increase yields – especially in countries with low yields and areas very prune to deforestation.

The current proposed regulation:

- Impose a ban on products from producers and countries, who have the option to make a big difference. A ban means that the EU is looking the other way and loses the opportunity for contributing to a green transition.

- This loss of opportunities actually means that the new regulation potentially has a higher environmental impact than business as usual.

Read more here: https://lca-net.com/p/4888

[1] https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_7444

Last month, on July 13th, the Natural Capital Coalition published their Natural Capital Protocol, which is a framework for performing Natural Capital Assessments “designed to help generate trusted, credible, and actionable information that business managers need to inform decisions”.

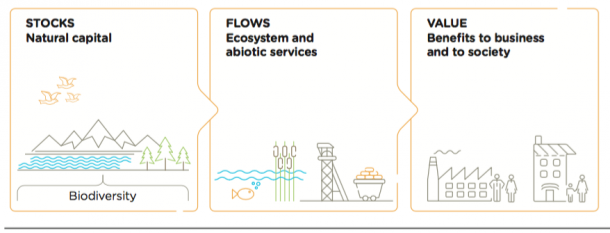

Natural Capital is defined as “The stock of renewable and non- renewable natural resources (e.g., plants, animals, air, water, soils, minerals) that combine to yield a flow of benefits to people”. These flows can be ecosystem services or abiotic services, which provide value to business and to society, and thus includes the impacts on human capital that go via impacts on natural capital (e.g. clean air). The Natural Capital Protocol thus covers the same issues as traditional biophysical Life Cycle Assessment (see also my March 2015 blog on the terminology of Natural Capital Accounting).

Figure 1.1 from Natural Capital Protocol (2016). Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The framework largely follows that of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), starting with the goal definition in Chapter 2: “Define the objective” including target audience and stakeholder engagement. The scope definition in Chapter 3 covers the determination of the focus (organizational, project or product), the extent of the life cycle perspective (here called “boundary”: cradle-to-gate, gate-to-gate, downstream), the stakeholder perspective (here called the “value perspective”: own business only, society, and/or specific stakeholder groups), type of valuation (qualitative, quantitative, monetary), and “other technical issues”: baselines, scenario alternatives, spatial and temporal boundaries.

The Natural Capital Protocol continues by describing screening (Chapter 4: Which impacts and/or dependencies are material?), inventory (Chapter 5: Measure impact drivers), impact assessment (Chapter 6 on the measurement of state changes, i.e. impacts), valuation (Chapter 7), interpretation (Chapter 8) and taking action (Chapter 9).

The largest difference to LCA seems to be the particular focus on what the Protocol calls Natural Capital dependencies, which is an optional risk assessment of the supply security and liabilities related to use of Natural Capital and the precautionary measures that the business takes to reduce these security and liability issues. Such a risk assessment should be part of normal business practice, but is not part of LCA, while the practical measures taken will be part of a life cycle inventory and the impacts of these measures are thus included in the LCA results.

For people familiar with LCA, the Natural Capital Protocol may not contain much new, but the Protocol is a good, simple introduction to environmental assessment from a business perspective and an important call for business to take action.

Reference:

Natural Capital Protocol (2016). Available: www.naturalcapitalcoalition.org/protocol