In May this year we proudly presented the third version of our wastewater inventory model, WW LCI, at SETAC Europe’s 29th Annual Meeting in Helsinki, Finland (see the presentation). This constitutes the 5th consecutive platform presentation about WW LCI in a SETAC conference, which is a good sign of the scientific interest that our model has received so far from the LCA community. We take this milestone as an opportunity to look back at the story behind our model.

The developme nt of WW LCI started in 2015 as one of our crowdfunded projects, together with the three companies Henkel, Procter & Gamble and Unilever. Our goal was to develop a model and Excel tool to calculate life cycle inventories (LCIs) of chemicals discharged in wastewater. The choice of partners for this project (consumer goods companies) was not a coincidence. Indeed, after use, many of their products, such as shampoos, washing detergents, etc., end up discharged in wastewater around the globe, which makes wastewater LCI modelling a necessity for these companies when carrying out cradle-to-grave LCA studies. Yet, the only commonly available LCI model covering this aspect to date was the one by my good friend Gabor Doka, developed for version 2 of the ecoinvent database. With our project, we aimed at overcoming several limitations of this model. First, we wanted our tool to describe wastewater as a mixture of individual chemical substances rather than a set of generic descriptors such as chemical oxygen demand (COD). Second, we wanted to cover several sludge disposal routes, namely landfarming, landfilling and incineration. Last but not least, we aimed to include the environmental burdens of untreated discharges, which are unfortunately still very common in developing countries. Before the end of 2015, the first version of WW LCI was ready, as well as an article that would ultimately be published the next year in the International Journal of LCA.

nt of WW LCI started in 2015 as one of our crowdfunded projects, together with the three companies Henkel, Procter & Gamble and Unilever. Our goal was to develop a model and Excel tool to calculate life cycle inventories (LCIs) of chemicals discharged in wastewater. The choice of partners for this project (consumer goods companies) was not a coincidence. Indeed, after use, many of their products, such as shampoos, washing detergents, etc., end up discharged in wastewater around the globe, which makes wastewater LCI modelling a necessity for these companies when carrying out cradle-to-grave LCA studies. Yet, the only commonly available LCI model covering this aspect to date was the one by my good friend Gabor Doka, developed for version 2 of the ecoinvent database. With our project, we aimed at overcoming several limitations of this model. First, we wanted our tool to describe wastewater as a mixture of individual chemical substances rather than a set of generic descriptors such as chemical oxygen demand (COD). Second, we wanted to cover several sludge disposal routes, namely landfarming, landfilling and incineration. Last but not least, we aimed to include the environmental burdens of untreated discharges, which are unfortunately still very common in developing countries. Before the end of 2015, the first version of WW LCI was ready, as well as an article that would ultimately be published the next year in the International Journal of LCA.

Shortly after the development of our model, we got in touch with Prof. Morten Birkved, from the Technical University of Denmark (currently at the University of Southern Denmark), who was involved in the development of SewageLCI, an inventory model to calculate emissions of chemicals through WWTPs. We decided to join forces and integrate the two models, eventually giving rise to the second version of WW LCI, thanks to the hard work of Pradip Kalbar, current Assistant Professor at the Centre for Urban Science & Engineering (CUSE) at IIT Bombay. Pradip’s work led to key improvements in WW LCI, such as the inclusion of wastewater treatment by means of septic tanks, tertiary treatment of wastewater with sand filtration, treatment of wastewater in WWTPs with primary treatment only, treatment of sludge by composting, as well as the integration in the tool of a database containing wastewater and sludge statistics for 56 countries. Also, Pradip was responsible for our second peer-reviewed publication, this time in the journal Science of the Total Environment.

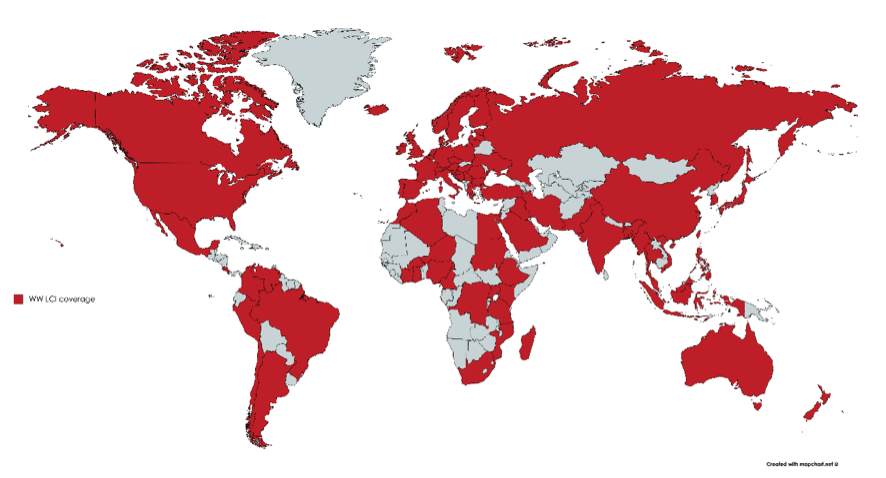

After some quiet time, in 2018 I decided to get to grips with several limitations of the model, such as the fact that it did not support discharges of metals in wastewater, but more importantly, I realized that by describing wastewater as a mixture of individual chemicals, as in e.g. a list of ingredients in a shampoo formulation, I was closing the door to many LCA practitioners who typically can only describe the pollution content in wastewater with the very generic descriptors I had rejected in the first place, namely COD, among others. Thus, I adapted the model to support metals as well as the characterization of wastewater based on the four parameters COD, N-total, P-total and suspended solids. On top of this, many additional features were implemented, mainly aimed at an improved regionalization, that is, to try and make LCIs more country-specific. Some of the improvements made included: emissions of methane from open-stagnant sewers, climate-dependent calculation of heat balance in the WWTPs, capacity-dependent calculation of electricity consumption in the WWTPs, the inclusion of uncontrolled landfilling of sludge, the specification of effluent discharges to sea water or inland water, and last but not least, expanding the geographical coverage of the statistics database from 56 to (currently) 86 countries, representing 90% of the world’s population (figure 1). The result of this effort, in short, is our third and latest version of WW LCI, presented in May at the SETAC conference.

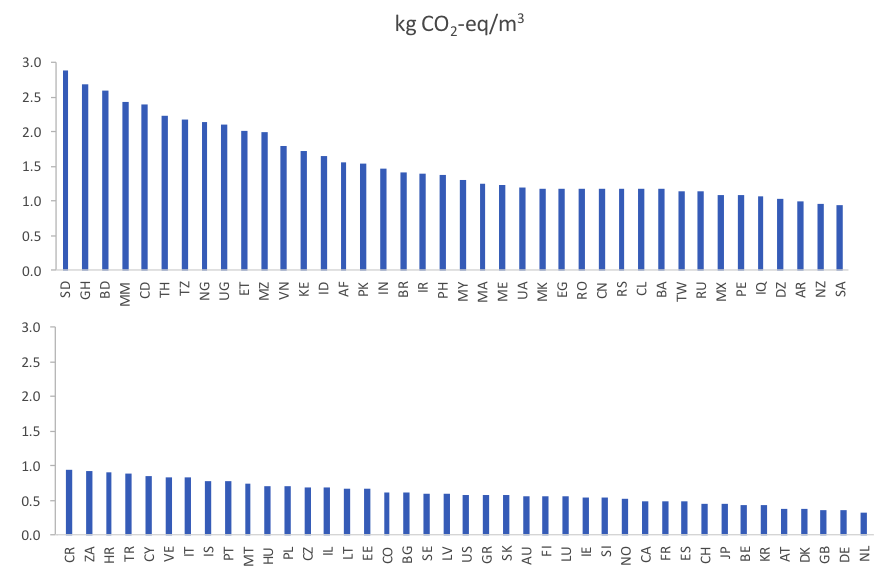

As an example of the current tool capabilities, the figure below (taken from the SETAC presentation) shows the carbon footprint of discharging 1 m3 of a typical urban wastewater in 81 countries. As it can be seen, there is wide variability between countries (up to a factor 6), with highest emissions in those countries where methane from open and stagnant sewers is expected to occur. On the other hand, emissions are substantially lower in countries where wastewater is properly collected and treated in centralized WWTPs. Obviously, the carbon footprint is not the only relevant metric, and WW LCI can support others just as well, including eco-toxicity.

Needless to say, WW LCI is not perfect. We can mention as main model limitations the fact that it does not address uncertainty, its data-demanding nature when used to model specific chemicals, the not-so-easy operation of the excel tool and the export of LCIs being currently limited to the software SimaPro. In spite of this, to our knowledge this is the most complete, flexible and regionalized inventory tool to model urban wastewater discharges in LCA studies and we expect it will eventually become the preferred approach for professional LCA practitioners. We are just a few SETAC presentations away from it.

Chemicals are ubiquitous. They are needed, directly or indirectly, for all products and services. In consumer products in particular, very often the fate of chemicals after consumer use is to be sent down the drain to municipal wastewater treatment plants (WWTP).

In these plants typically they are subject to biological treatments leading to their degradation, and to the discharge of the degradation products to the environment. However different chemicals behave differently in WWTPs, depending on their physical- chemical properties and biodegradability. An accurate modelling of the life cycle impacts of chemicals requires taking into account this specific behaviour in a WWTP, namely whether a chemical will be:

WWTPs have been extensively assessed by means of LCA. Besides case studies on particular plants, some models are available which allow the practitioner to obtain the inventory for treating a wastewater that has a particular pollution load. The best example of this is the model developed by Gabor Doka for the ecoinvent database, programmed in Excel (Doka 2007). With this tool it is possible to quantify the inputs (chemicals, energy, etc.) and outputs (emissions to air, water, soil) from treating wastewater, including not only the WWTP itself but also sludge treatment through incineration or spreading on farmland.

However, the major drawback of this model, when applied to chemicals, is that it considers the average fate of chemical elements in typical municipal wastewater. Thus this tool cannot be used to accurately reflect the fate of specific chemicals or chemical mixtures in a WWTP.

To alleviate this we have, together with Henkel and Procter & Gamble, started the wastewater LCI initiative with the aim of developing a model to calculate life cycle inventories of chemical substances sent down the drain, taking into account wastewater treatment, sludge disposal, and degradation in the environment (see figure 1). This project is established as a club to which anyone can subscribe. The wastewater life cycle initiative is administrated by 2.-0 LCA consultants. For more information and subscription, please contact 2.-0 LCA consultants: https://lca-net.com/clubs/wastewater/

Doka G (2007), Life Cycle Inventories of Waste Treatment Services. Final report ecoinvent 2000 No. 13, EMPA St. Gallen, Swiss Centre for Life Cycle Inventories, Duebendorf, Switzerland.