The European Union Product Environmental Footprint (PEF) method “to measure and communicate the life cycle environmental performance of products” was updated in December last year and is now widely promoted by the Commission. More and more customers now ask us to have their Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) performed according to PEF. Yet, we still recommend our customers to settle for an ISO 14044 compliant LCA, while we wait for the PEF method to be further improved. This blog-post seeks to explain why.

A major problem with the current PEF method is the lack of consistency of the rules across different product categories. For each product category, there are separate rules, known as PEF Category Rules (PEFCRs), developed by Technical Secretariats that each represent industries that cover at least 51% of the European consumption market for the product category. The result is that we now have as many rules for how to make an LCA as there are product categories. This limits the relevance of the results to comparisons within each product category and creates potential conflicts with similar (but different) rules developed by industries outside Europe, and thereby with the WTO-rules. But in reality, most of the content of the PEFCRs regulate issues that could better be (or are already) addressed as general requirements for all products instead of having to be included in each and every single PEFCR. Examples include requirements on including capital goods and infrastructure, product lifetimes or standardized methods of computing lifetimes, the depreciation method to allocate the burden of capital goods over their service period, requirements for scenarios for use and End-of-Life, requirements on the use of primary data and the age of data, data sources, impact assessment methods and indicators, cut-off criteria, use of best estimates versus worst-case, requirements and assessment methods for data quality, and methods for handling multi-functionality. For each of these issues, the 2021 PEF methodology gives preferential status to the specific rules or the PEFCRs over the generic requirements of the PEF method, thereby furthering inconsistencies and hampering cross-category product comparability. We recommend instead to apply the same rules for all products, thus limiting the content of PEFCRs to only include issues for which it is meaningful that different product categories can have different requirements that are not more consistently regulated at the generic level of the PEF methodology for all products. This would not only allow consistent cross-category product comparisons, but also imply a considerable streamlining and significant cost-saving for maintaining the PEF system and for the construction of a harmonised and consistent database. The less prominent role of PEFCRs will also allow for better participation of the scientific and civil society, and reduce undue influence from industries within a specific product category.

Another major problem with the current PEF method is the lack of harmonisation with international standards, to ensure that calculations provide reliable and credible information for fair comparisons, preventing that claims based on the PEF method can be misleading and lead to litigation. In our view, the core understanding that all further rules should be based on, is that expressed in ISO 14040:2006, annex A.2:

“applications relate to decisions that aim for environmental improvements, which is also the overall focus of the ISO 14000 series. Therefore, the products and processes studied in an LCA are those affected by the decision that the LCA intends to support.”

An illustrative example of how the 2021 PEF revision is breaking away from this core understanding is the way that the earlier requirement to use the ISO 14044 allocation hierarchy is now immediately negated by an exception in the following sentence: "Specific allocation requirements in other sections of this method always prevail over the ones available in this section". Other sections then require the use of special rules, e.g., for different agricultural, slaughterhouse, and recycling situations. We recommend to harmonise and improve the realism of the modelling of the multi-functionality of processes by adjusting the PEF 'circular footprint formula' as described in Schrijvers et al. (2021) and requiring its consistent use for all situations of multi-functionality and use of recycled materials and energy, while simplifying the description by providing separate requirements for each real-life situation and making clear references to the ISO 14044 allocation hierarchy. Furthermore, we recommend to harmonise and improve the realism of the linking of unit processes into product systems by adding precise requirements and guidance on system expansion and the identification of the upstream system for intermediate product inputs, based on the description provided in ISO 14044 Annex D.2.1.

While ISO 14044 only allows to leave out parts of the life cycle on grounds of insignificance, the PEF methodology document does not have such strict completeness requirements for the activities to be included. Although 'completeness' is one of the data quality requirements for PEF compliant data sets, this is in reality only a requirement to include all 16 PEF impact categories, while data gaps in the system model as such are allowed as long as 'transparently reported' and 'validated by the verifier'. However, even when transparently reported and validated, data gaps will constitute a complication for comparability between studies. The 2021 PEF method explicitly recommends excluding capital goods (incl. indirect land use) unless a clear and extensive explanation is provided for why the inclusion of capital goods (including infrastructure) is relevant. Considering that comparable products can come from very different product systems that have very different use of capital equipment, this introduces a significant potential for biased comparisons across different products, as quantified by Font Vivanco (2020). Similarly, unbiased comparisons that involve products from forestry and agriculture cannot be done without including indirect land use as an important source of biomass production capacity, a necessary capital good for forestry and agriculture. Interestingly, the mandatory format guide for EF compliant data sets requires capital goods to be included unless clearly documented and checked by the reviewer. Of these conflicting requirements, the latter is obviously the more relevant. We recommend to follow to the ISO 14044 requirement that parts of the life cycle shall only be excluded on the grounds of insignificance, to remove the allowances for data gaps and exclusion of capital goods, and enforce the (existing) requirement that all non-elementary flows shall be modelled up to the level of elementary flows (flows either drawn from the environment without previous human transformation or released into the environment without subsequent human transformation), and finally to add a requirement to check the system completeness by applying mass balances ('what goes in must come out').

The PEF method requires the use of 16 specific impact categories and a single overall score based on weighting factors that are not based on a science-based elicitation procedure. Reporting additional impact assessment results as additional information is prohibited. While this strict enforcement of a specific impact assessment method does increase comparability between products, it would be preferable if this was based on the latest scientific evidence. We therefore recommend to replace the current PEF normalisation and weighting factors with those recommended by the international UNEP-GLAM project, and to allow the results from scientifically based cause-effect models, such as for example Global Temperature Potentials, to be reported under 'Additional environmental information'.

The 2021 PEF method includes a data quality scheme that requires a specific software to provide an overall data quality score without any empirical basis and has no relation to the resulting additional uncertainty that stems from lacking data quality. Without the ability to convert data quality into uncertainty, the PEF study results lack an important feature for decision support. We recommend instead to apply empirically confirmed average uncertainty values for each data quality score, based on the method of Ciroth et al. (2016), so that uncertainty from low quality data can be added to the basic uncertainty of each flow and thus included in the overall uncertainty propagation when calculating LCA results for each product.

In addition to the above issues, the 2021 PEF method includes a large number of unnecessary and/or burdensome requirements that effectively hampers its practical application. In fact, we have yet to see an LCA study that have fulfilled all the PEF requirements. What most practitioners do today, is to say: “We have followed the PEF standard as far as possible”, which is not really a way to ensure consistency and comparability. To make the PEF method operational in practice and reduce unnecessary costs, we therefore recommend to remove or reword these PEF requirements:

We have raised these issues and made the above recommendations in a recent report to the European Parliament, and will continue to gather support for a corresponding revision of the PEF method to make it reliable, fair, and practicable.

When systems have more than one product, the ISO standards on LCA recommends avoiding partitioning/allocation of the system by instead “expanding the product system to include the additional functions related to the co-products” (ISO 14044, clause 4.3.4.2).

I am sometimes asked: “Is this ‘system expansion’ of ISO not something different from the ‘substitution’ approach (also sometimes described as the ‘avoided burden’ approach) used in consequential LCA?” This lack of clarity in the ISO standards is also sometimes lamented in the literature, e.g. by Brander & Wylie (2011).

This makes me miss the very clear Figure B.2 that we had in the original ISO 14041:1998 (which was merged with ISO 14042 and 14043 into the current ISO 14044 in 2006). This figure illustrated clearly that the authors of the ISO 14040 series viewed system expansion as a substitution. Unfortunately, the informative annex in which this Figure B.2 was placed did not survive the merger. Since few nowadays have direct access to the original ISO 14041 text, let me share this with you:

EXAMPLE 3: Utilizing the energy from waste incineration.

One of the widely used examples of avoiding allocation by expanding the system boundaries is when utilizing the energy output from waste incineration as an input to another product system.

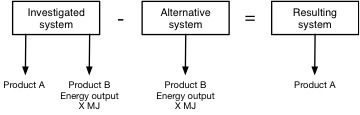

The allocation problem arises because the investigated product system has two outputs: the product or service investigated (A) and the energy output from incineration (B). This allocation problem is often solved by expanding the system boundaries, as illustrated in Figure B.2.

Figure B.2 – Expanding system boundaries for waste incineration

End of quote from ISO 14041:1998

As you can see clearly from the figure, the expansion is done by subtracting the alternative system. Mathematically, subtraction is the same as a negative addition. There are also additional examples of this in Figure 15 and 16 in ISO 14049 (entitled “Illustrative examples on how to apply ISO 14044 to goal and scope definition and inventory analysis”).

But the fact that this discussion pops-up from time to time just goes to show the current ISO 14040/44 sometimes fail us in its role as a standard, that is, to minimize or eliminate unnecessary variation (more about that in Weidema 2014).

References:

Brander M, Wylie C. (2011). The use of substitution in attributional life cycle assessment. Greenhouse Gas Measurement and Management 1(3-4):161-166. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/20430779.2011.637670

Weidema B P (2014). Has ISO 14040/44 failed its role as a standard for LCA? Journal of Industrial Ecology 18(3):324 326 https://lca-net.com/p/1273

Last week, I spent 20 hours making more than 30 pages of comments to the three draft guidelines from the FAO Livestock Environmental Assessment Performance (LEAP) Partnership. They are currently in public hearing until July 31st. You can find my comments in our executive club, if you are a club member.

There is already a large number of guidelines that interpret the basic ISO 14040/44 standards for LCA for specific products, countries and/or impact categories. Every time a new one is made, there is the risk of introducing new inconsistencies (see Weidema 2014) although each new guideline sets out with the praiseworthy intention to provide consistency and harmonisation - in the case of LEAP for environmental performance assessment and monitoring of livestock supply chains on a global scale. If we should make comments on all the guidelines that are continuously being produced, we should have a full-time person or more for this task alone. But in the case of FAO, I made an exception - like I previously did with the EU product environmental footprint guideline - since I regard FAO as an important public-service organisation with a large international impact.

And although it was a lot of pages to read and comment - with some unavoidable redundancy due to the three parallel guidelines for feed, poultry, and small ruminants - I found it worthwhile, since the guidelines actually contain quite some default data and assumptions, for example for nitrogen excretion from chicken and laying hens, that will hopefully lead to less arbitrariness when applied in future studies.

But with more than 30 pages of comments you can imagine that I have not been entirely happy with the current state of the drafts. At the most fundamental level, it does not seem wise for an international guideline to adopt an attributional modelling approach that cannot be used for decision support. The main problem of the attributional approach is that the results cannot be used for decision support regarding improvements of the analysed systems, simply because the results do not reflect the environmental consequences of such improvements. The results will be misleading if they by mistake should anyway be used for decision-making. The authors appear to be unaware that an attributional approach cannot say anything about the environmental performance of a product, only about the environmental performance of that part of the product system that is included according to the chosen allocation rules for by-products. This is why ISO 14040/44/49 recommends the use of system expansion to avoid allocation, and generally describes a consequential approach to system modelling. The main reason for this is that ISO 14040/44/49 is intended for supporting improvements, which requires LCAs that provides information on the consequences of these improvements.

And you will probably not be surprised that I am also not happy with the deviation from the ISO hierarchy for handling co-products, where the draft LEAP guidelines m ix system expansion and allocation. Mixing these approaches in the same study leads to the result being neither attributional nor consequential. System expansion is not relevant for attributional questions and allocation is not relevant for consequential questions. Each allocation method provides an answer to a specific question, so when combining several different allocation methods within the same study, both the question and the answer is obscured. Consistently applying system expansion for joint production and subdivision by physical causality for combined production provides an unambiguous answer to the question of the consequences of a decision, which is the purpose of the majority (if not all) LCAs.

The FAO text here suggests that there are situations where system expansion cannot be applied because the avoided production cannot be unambiguously identified. However, since the input to a market is identified by the same procedure whether the market output is decreasing (avoided inputs) or increasing (normal inputs), the avoided production can always be determined with the same degree of (un)ambiguity as any other market input to the product system. If the procedure that is generally accepted for identifying upstream market inputs is discarded just because the sign of the flow has been inversed, this places into question the entire procedure by which we link our product systems, and can therefore not be used as an argument for not applying the procedure specifically for avoided production.

And then there are all the things that are not included in the guideline even though these are exactly the kind of things that would have been relevant. Such as how to determine the temporal boundary between two subsequent crops with an intermittent fallow period, or how to deal with biogenic carbon (excluded, which is not in line with ISO 14067).

These were just some of the many issues that hopefully will be corrected in the final version. Which is why such public hearings are so important.